Today, in this brief article, we will attempt to understand what the general style of expression of Shaykh al-Akbar Muhyiddin Ibn al-Arabi is. And is it truly as difficult to understand the Shaykh’s discourse as common people believe? The question also arises: what is the core issue that even many among the People of Tasawwuf (Sufism)—who possess an understanding of its fundamental principles—still cannot reach the original intent within the Shaykh’s words? Even if a superficial point is understood, they feel themselves strangers to the true depth of the Shaykh.

These questions are not new for us. We have now spent nearly twenty years working on the sciences of Shaykh al-Akbar, researching his original Arabic texts, and translating his monumental works into the Urdu language. This long and fascinating journey has given us the opportunity to understand the root causes of the difficulties encountered in comprehending the Shaykh and how to resolve them. Let us try to understand these reasons within the context of the Shaykh’s style, and at the end, we will also present its solution before you.

The General Style of Shaykh al-Akbar: A Universe of Meaning

When we open the sacred pages of the books of Shaykh al-Akbar, we find his written tradition divided into two distinct periods:

The First Style

This was when the Shaykh cast his unveilings (kashf) and realities in a poetic style. This choice was not merely coincidental. The reality is that Shaykh al-Akbar was a poet of consummate skill even before he was a Sufi. From his boyhood, he had already established his poetic identity in the literary circles of Andalusia. It is a well-established historical fact that the Shaykh participated in Arab gatherings where poetry held a central status. In this regard, we find testimony in Ismail ibn Sawdakin’s book, Malfuzat Ibn al-Arabi:

He writes: “That day I had met Uthmani… and he was a poet. He said to me: ‘I want you (Ibn al-Arabi) to explain the meanings of an elegy (ritha’) to me so I can compose a poem for a person who has requested that I write an elegy for him using the meter of this ode by al-Mutanabbi:”

أَيا خَدَّدَ اللَّهُ وَردَ الخُدودِ

وَقَدَّ قُدودَ الحِسانِ القُدودِ

“I (Ibn al-Arabi) said to Uthmani: ‘Who has asked you for this elegy? So that I may know his status and tell you meanings appropriate for him.’ After that, I told him a verse which became the first line of that poem, and it was this:”

أيَا عَيْنُ وَيْحَكِ بِالدَّمْعِ جُودِي

فَإِنَّ الحَبِيبَ ثَوَى فِي اللَّحُودِ

This incident proves that before coming to Tasawwuf, the Shaykh was fully acquainted with the technical intricacies of Arabic poetry, possessed a masterful command over the subtleties of word and meaning, and was proficient in poetic terminologies (meter, rhyme, elegy). This is precisely why, when the doors of unveiling (kashf) and inspiration (ilham) opened upon him and he wrote symbolic books like Kitab al-Isra‘, Ismail ibn Sawdakin said: “O my master! I see this book as confined to the world of imagination (alam al-khayal)?”

The Shaykh’s response to this was a key clarification. He said:

“This unveiling came to me in the form of abstract meanings (mujarrad ma’ani), and most of my unveilings are like this. Then, Al-Haqq (The Truth, Glory be to Him) granted me the power to mould those meanings into expression (‘ibarat) and confine them in forms (suwar). Therefore, I have expressed these meanings in symbolic expressions in such a way that it has become like a dream, which only one who is acquainted with its principles can interpret.”

This is the Shaykh’s first unique style, which he deemed appropriate for expressing the realities of unveiling. This style resembles what we might call poetic prose or free verse, where he used rhymed and rhythmic prose (musaja’ and muqaffa), expressed the meanings of unveiling through dream-like allegories, and smoothed the path to realities through metaphors (istiarat).

Regarding this style, he says: “For example, by ‘our heaven and earth’, I do not mean this heaven and earth; my intention could be, for instance, ‘height’ and ‘lowness’.” Similarly, he takes ‘earth’ to mean the body (jism) and ‘heaven’ to mean the spirit (ruh). He also uses the sun and the moon in this metaphoric sense, where the sun is the spirit and the moon is the self (nafs). In his book Kitab al-Isra‘, he used ‘Andalus’ for ‘Dalas’ (i.e., darkness) and ‘Bayt al-Maqdis’ (Jerusalem) for the purity of the heart (qalb).

In the same book, he said: “I have come from the lowest place (a’la maqaanin adall), and I am a traveler to the City of the Messenger (madina al-rasul), a seeker of the Most Manifest Station (maqam azhar) and the Red Sulphur (kibrit al-ahmar).” Here, the “lowest place” alludes to Asfal al-Safilin (the lowest of the low), and the “City of the Messenger” is a metaphor for the Muhammadian Station (maqam Muhammadi). Similarly, later on, he speaks of three veils (hujubat): the Red Ruby (yaqut al-ahmar), the Grey Ruby (yaqut al-ashhab), and the Yellow Ruby (yaqut al-asfar); he himself later explained that the red is for the Essence (Dhat), the grey for the Attributes (Sifat), and the yellow for the Actions (Af’al). Likewise, the term Majma’ al-Bahrayn (Confluence of the Two Seas) – its outward meaning refers to the meeting of two seas, but the Shaykh intended by it the union of the spirit and the body (ruh wa jism). These and countless other examples of this nature bear witness that in his early period, the Shaykh used a poetic style to express the realities of unveiling.

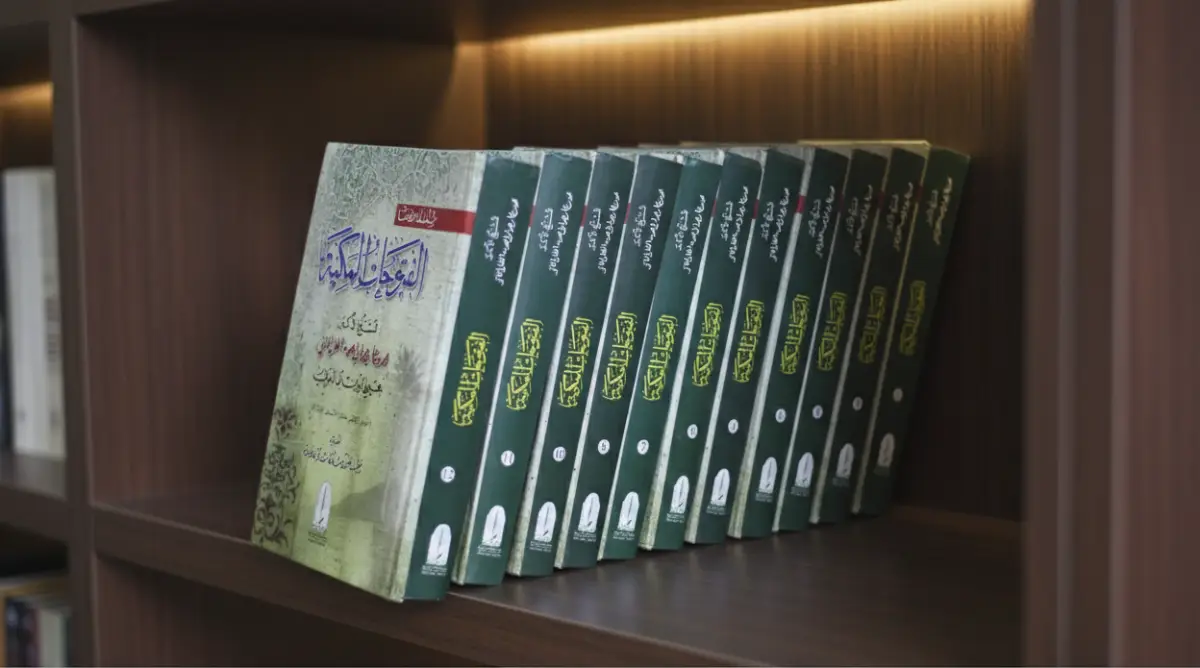

This mode of writing is most prominent in his early works, such as Kitab al-Isra‘, Anqa’ Mughrib, parts of Mawaqi’ al-Nujum, Mashahid al-Asrar al-Qudsiyyah, etc. Similarly, the epistle Taj al-Rasa’il wa Minhaj al-Wasa’il, written in Mecca, and a few works from later periods also belong to this style, including Al-Tanazzulat al-Mawsiliyyah and certain sections of the Futuhat al-Makkiyyah.

The Second Style

Similarly, in most works written after 595 AH, the Shaykh adopted a second style. In this style, he focused on coining terminology (istilahat) to interpret those unveiled realities. Previously, he had been writing about them in the language of symbols and metaphors, but now he began to record them according to rational measures. In this regard, he writes in the introduction to his book Insha’ al-Dawa’ir:

“When Allah Almighty acquainted me with the essential realities of things, their mutual relations and attributions, I decided to mold these abstract realities into sensory forms and diagrams for the convenience of my companion, Abdullah Badr al-Habashi, so that it would be easier for my companion and friend Abdullah Badr al-Habashi to understand them. And so that this could also become clear to everyone who has not reached them through unveiling, or whose limited intellect is incapable of perceiving them.”

The primary objective of Shaykh al-Akbar with this new style was, firstly, to bring abstract realities closer to human understanding for those of weak insight, and secondly, to make those with superficial thinking comprehend their true station within existence. To achieve this purpose, he gave tangible form to intellectual concepts through diagrams, circles, and tangible examples—thus adopting a revolutionary style in his discourse. This approach was entirely different from his poetic, symbolic style. In contrast to the abundance of metaphors and symbols, it gave central importance to the precise definition of terminology. The defining boundaries of every new term (a’yan thabita [fixed entities], al-insan al-kamil [the perfect man], al-hadrat al-ilahiyya [the divine presences]) were clarified, and philosophical truths were presented with logical coherence.

The new terms coined in this style of the Shaykh were so numerous that the contemporary researcher Dr. Su’ad al-Hakim had to write a book, Muwallid Lugha Jadida (Generator of a New Language), to count them. Later, in her book Al-Mu’jam al-Sufi (The Sufi Lexicon), she also provided their detailed explanations. This work is a testament to the fact that Ibn al-Arabi not only gave new terminology to Tasawwuf but also played his role in expanding the Arabic scholarly language.

To deliver this very intellectual legacy of Shaykh al-Akbar to the Urdu-speaking audience, work has also begun under the Ibn al-Arabi Foundation on the “Jami’ Istilahat Ibn al-Arabi” (Comprehensive Compendium of Ibn al-Arabi’s Terminology) project. The goal of this project is to compile all of the Shaykh’s coined terms, propose Urdu equivalents for most of them, and provide an explanation of each term and the context of its coinage, so that the Urdu-speaking student can also gain direct access to the terminological system established by this great Sufi.

This terminological style of the Shaykh was not merely a “mode of expression”; it was an effort to establish Tasawwuf on scholarly foundations. Where in the first period he had adopted the language of symbol and imagery, he now molded the sciences of Tasawwuf into a documented system through a lexicon of terms, explanatory diagrams, and logical definitions—a system that remains the final word in the scholarly formation of the world of Tasawwuf to this day.

Whats the difficulty?

Now, let us try to understand why comprehending these two styles of the Shaykh is difficult for the general reader. According to our extensive experience of study and translation, the reasons can be condensed into five main points:

1- The Veil of Literalism

The first reason was stated by the Shaykh himself:

“When I say ‘heaven and earth’, I do not mean this material heaven and earth, but rather the meanings of ‘height’ and ‘lowness’.”

However, the problem is that the general religious reader is often trained within the confines of literal words. They are conditioned to consider the lexical meaning as final. When they take the Shaykh’s metaphors in their literal sense, they get stuck on the external words. Access to the inner (batini) meaning becomes impossible, and consequently, they face disappointment and disillusionment.

2- The Abundance of Metaphors

The second reason is the sheer abundance of metaphors. If a piece of writing contains a few metaphors, there is still room for the reader to understand them. But when the style itself is such that every sentence is laden with symbols and metaphors, and every word is wrapped in multiple layers (e.g., Sun = Spirit, Moon = Self, Red Ruby = Divine Essence), then reaching the intended meaning becomes no easy task. When the entire text becomes a jungle of metaphors, what is the poor reader to do? Thus, they cannot unlock this door with a single key and lose their way from the original meaning and intent.

3- The Lack of Experiential Unveiling

Since the Shaykh’s writings are often the direct result of unveilings (kashfi mushahadat) and inspired revelations (ilhami waridat), this language transcends the sequence of logical reasoning and is a product of a specific “state” (hal) or “station” (maqam). For a reader who is not acquainted with that “state,” it is impossible to weigh this language solely on the scales of the intellect. Just as a description of the taste and aroma of food is meaningless to a hungry person who has not eaten, the language of unveiling is incomprehensible to a reader unfamiliar with inner spiritual states.

4- Unfamiliarity with the Realities and Terminology

The fourth reason is also a lack of acquaintance with the realities and the Shaykh’s specific terminology. To clarify his unique concepts, the Shaykh established a sophisticated system of terminology, such as al-Haqq (The Real), al-Khalq (The Creation), Barzakh (The Isthmus), Alam al-Mithal (The World of Similitudes/Imaginal Realm), al-Insan al-Kamil (The Perfect Human), and A’yan al-Thabita (The Fixed Entities). If the reader is not familiar with this terminological system of the Shaykh, they are left trying to break a lock without a key, fumbling in the dark.

5- The Comprehensiveness and Vastness of Concepts

Ibn al-Arabi’s circle of knowledge is astonishingly vast. The Qur’an and Hadith, Jurisprudence (Fiqh) and Theology (Kalam), Philosophy and Logic, Astronomy and Numerology, and the sciences of various religions—all converge in his works. While discussing a single issue, he speaks within the references and context of all these fields, which causes confusion for the unacquainted reader.

What Should a General Reader Do in This Regard?

The difficulties in the writings of Shaykh al-Akbar are undeniable, but it should never be assumed that these sciences are incomprehensible. If that were the case, then the Shaykh’s vast intellectual treasure would be merely futile and wasted. Based on my research and observation, if a general reader takes the following scholarly steps, it is possible that they too may join the group of elect (khawass) for whom these sciences were intended.

1- Acquaintance with Religious Sciences

First and foremost, one must develop a habit of studying the Islamic sciences (Ulum al-Islamiyyah). One must acquire knowledge of the Qur’an and Hadith, gain familiarity with the principles (usul) and methodologies (manahij) of Tafsir (exegesis), and become capable of understanding the language of Ahadith, their transmission (riwayat), critical analysis (dirayat), and the sciences of Hadith. One should undertake a comparative study of different schools of jurisprudence (fiqhi makatib-e-fikr) and not confine oneself to the restrictions of a single sect or school of thought, for after reading the Shaykh, one must ultimately transcend these confines. Similarly, it is essential to be knowledgeable about the basic concepts of Tasawwuf, such as Tazkiyah-e-Nafs (purification of the self), Maqamat wa Ahwal (spiritual stations and states), Shari’ah and Tariqah, and Suluk wa Safar (spiritual journeying). One’s study should be sufficient to not only understand the basic terminology of these sciences but to immediately recognize them when alluded to. This will provide a foundation that will later assist in understanding the sciences expounded by Shaykh al-Akbar.

2- Begin with the Shaykh’s Easier Books

Once this scholarly foundation is solid, one should then begin their study with the Shaykh’s relatively easier books—those not saturated with metaphors and allusions, nor buried under the weight of intricate terminology. For example, one can study his books on the science of Hadith, like “101 Ahadith Qudsi” or “Al-Mahajjah al-Bayda” (though note: Al-Mahajjah al-Bayda is actually by Imam al-Ghazali; this might be a reference to another text or a slight error in the original). To learn about self-reformation and the states of the great saints, one can read “Ruh al-Quds fi Munasahat al-Nafs” and “Mukhtasar al-Durrah al-Fakhirah.” To understand the correspondence between the macrocosm (alam al-akbar) and the microcosm (alam al-asghar) and the divine managements (tadbirat) in reforming this human kingdom, one can read “Al-Tadbirat al-Ilahiyyah.” Most parts of “Mawaqi’ al-Nujum” are written in simpler language and will be helpful. One must absolutely read the final chapter of the “Futuhat al-Makkiyyah.” All these books will introduce the reader to the Shaykh’s style; they will begin to get a sense of his terminology and approach. Once they have gradually read these, moving on to the rest of his books will become easier.

3- Familiarity with the Shaykh’s Terminology

When a reader gains access to the sciences of Shaykh al-Akbar through the easier books mentioned above, the biggest test is that of terminology. There is no room for error here, because the traditional meanings of words used in general religious literature (like ‘Aql [Intellect], Qalb [Heart], Ruh [Spirit], Barzakh [Isthmus]) are deeply ingrained in the mind. The reader instinctively imposes these familiar meanings onto the Shaykh’s terminology, even though the Shaykh has assigned his own specific meanings to these very words within his sciences.

The solution is to take these three practical steps:

First, find the author’s definition of the term, as the Shaykh has provided explanations for every important term throughout his books. The translator might have provided this definition in a footnote or an endnote. In such a case, memorize it so that whenever the term appears, you know its defined meaning.

Second, create your own personal terminological glossary. Write down the Shaykh’s terms and their definitions in a diary or notebook. This will not only help you understand them but also allow you to refer back to them when needed.

Third, pay special attention to the context (siyaq o sabaq). It has been commonly observed that the Shaykh has established dozens of meanings for a single term. If you fail to grasp the contextual clue (qarinah-e-kalam) and apply the wrong meaning, you will certainly err.

A perfect example is the word “‘Ayn” (عین), which holds numerous meanings in his works, including: Existence (Wujud), Reality (Haqiqat), Eye (‘Ayn), Source (Sarchashmah), Essence (Zat), Non-Existent Entity (Adami Wujud), Fixed Entity (‘Ayn Thabit), and many others. If the reader does not apply the correct meaning within the right context, they will inevitably make a mistake.

“The terminology of Shaykh al-Akbar is not made of dead lexical words, but of living existential realities. When you look up ‘Ayn’ in a dictionary, you find it means ‘eye,’ but when you read it in the Shaykh’s context, it appears as ‘existence’ and ‘reality.’ Grasping this difference is the first step to true gnosis (irfan).”

4- Connect with a Teacher

No matter how much progress you make in understanding the sciences of Shaykh al-Akbar, the feeling persists at every moment that this is an shoreless ocean, not a small pool whose bottom can be reached. This is precisely why the tradition of writing commentaries (shuruh) on these texts has continued since the very beginning—the fact that there are over 150 commentaries on the Fusus al-Hikam alone is a telling testament to this. However, the tragedy is that most of these commentaries are in Arabic, leaving the Urdu, Persian, and Turkish-speaking audiences deprived of them. To make matters worse, some commentators have made the system of terminology even more complex, causing the reader to get lost in a labyrinth of terms instead of understanding the point, thus severing their direct connection with the text.

In such a situation, the only solution is a teacher (ustad). Shaykh al-Akbar himself said: “This knowledge of mine is like a dream, which only an interpreter (mu’abir) can understand.” Based on this very principle, a teacher is needed who is not only familiar with the external dimension of the Shaykh’s sciences but has also embodied these realities in their life through practical spiritual wayfaring (suluk). A teacher who does not teach words as dead concepts but leads one to the taste of existential realities (wujudi haqa’iq).

In light of these very necessities, the historic series of the “Ibn Arabi Baithak” (Ibn Arabi Session) was established five years ago—a unique scholarly environment where the profound sciences of Shaykh al-Akbar are translated into the contemporary language and delivered to general seekers. In this Baithak, complexity is transformed into simplicity. The Shaykh’s intended meanings are presented in easy language. Texts are read word for word, and distortion of meanings is avoided. The central presidency of this Baithak is held by Mr. Abrar Ahmed Shahi, and while formal permission is required for physical attendance, you can participate live online from anywhere.

5- Engage in Practical Tasawwuf

The sciences of Shaykh al-Akbar are not some abstract philosophy that is sufficient to merely understand. It is a path of spiritual wayfaring (rah-e-suluk) which, when walked, leads to the Truth (Haqq). It is a practical code of life (zamadaqa-e-hayat) that one must immerse their soul and body into; it must be seated in the heart, and one must align their outer and inner being with it. At the conclusion of his book Al-Tadbirat al-Ilahiyyah, the Shaykh himself says:

“O seeker (murid), know the salvation of your self (nafs). First of all, find for yourself a teacher who shows you the faults of your self, who liberates you from the servitude of your self, even if you have to travel to distant lands for him.”

Since Tasawwuf today comprises numerous paths (turuq) and countless approaches (mashrab). Each path is established on the principles laid down by its founder, and the masters of the path (piran-e-tariqat) provide guidance to disciples (salikin) according to their method. Therefore, it is best that if you desire complete access to the Shaykh’s sciences and gnosis (ma’arif), you should join his path. For only then will you be able to connect this theoretical knowledge (‘ilmi) with practical wayfaring (amali suluk). Then, the Futuhat al-Makkiyyah will not remain merely a book but will become the mirror of your inner self and the curriculum of your life. You will transcend the debate over the literal understanding of the intricate phrases of the Fusus and instead witness its practical lessons. Where the Truth (Haqq) will no longer be a mere thought or tale, but an observation of constant presence (huzuri). You will attain that knowledge of the Truth (ma’rifat) which is neither written in books nor spoken by tongues. On the Shaykh’s path, you will see all of this happening within yourself. This is the station where you will attain that knowledge of the Truth hidden in the saying: “Man ‘arafa nafsahu faqad ‘arafa rabbahu” (Whoever knows himself knows his Lord).

Alhamdulillah, the process for practical initiation into the Shaykh’s path (Tariqa) has also begun in Pakistan. And with the permission of Shaykh Ahmad Muhammad Ali, we are now formally initiating people into this path. In this path, remembrance (dhikr wa azkar) and prescribed practices (a’mal) for the disciple (murid) are taught in accordance with the concepts found in the Shaykh’s books, and it is a beautiful amalgamation of the outer (zahir) and the inner (batin).

After going through all these stages, the hope is that you will not only understand the Shaykh’s discourse but will also become capable of explaining it to others.

Article Writer: Abrar Ahmed Shahi

President, Ibn al-Arabi Foundation

https://abrar.ibnularabifoundation.org