This introduction was first published in 2011, then corrected and republished in 2025.

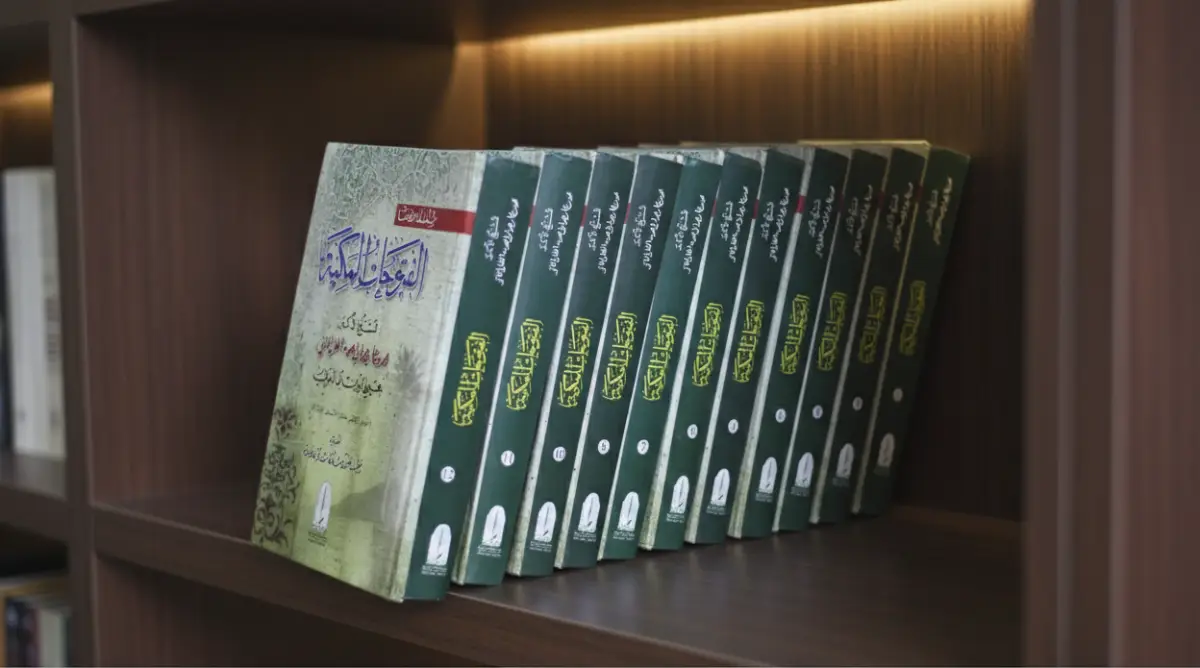

A New Milestone in Ibn Arabi Studies: Yemen’s Critical Edition of Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya

The book “Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya” (The Meccan Revelations) is considered the most important work of the great master (al-Shaykh al-Akbar) Muhyi al-Din ibn al-Arabi. It can now be said that it represents the first Sufi encyclopedia, and the primary reference for all Sufi knowledge after the Holy Quran and the Prophetic Hadith—without dispute.

The great master began authoring this book of his in Mecca the Honored in the year 599 AH, and he finished it in Damascus in the month of Safar in the year 629 AH. Upon its completion, he mentioned: “This is the original in my handwriting, for I do not work on a draft for any of my compositions.”

However, in the year 632 AH, the Shaykh al-Akbar decided to rewrite this encyclopedia in his own hand, considering the first version as a draft. He deleted from it and added to it. His work took 4 years, finishing in the year 636 AH. The book then emerged in its final, revised form, thereby being an authentic expression of the summary of his vision and experience after he had reached the age of seventy-two.on:

Book Description

The book consists of 37 fascicles, and its total number of pages is 10,860, of which 316 are blank and 10,544 are written. When these pages were photographed, the illustrations were taken at a rate of one plate for every two facing pages. The number of these plates, or the new paired pages, became 5,430, of which 158 are blank and 5,272 are written.

This new Edition:

The recent publication of a new critical Arabic edition of Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya (The Meccan Revelations) by the Ministry of Culture of Yemen represents a watershed moment for scholars and devotees of Shaykh al-Akbar Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi. This monumental work, edited by Abd al-Aziz Sultan al-Mansub with Ahmed Saeed al-Nasir, sets a new standard for accuracy and comprehensiveness in accessing Ibn Arabi’s magnum opus. For the Ibn al-Arabi Foundation, which has dedicated itself to producing meticulous editions and translations of the Shaykh’s works, this publication marks an extraordinary advancement in the field of Akbarian studies. The Foundation has long recognized the urgent need for a reliable text of the Futuhat, as it forms the cornerstone of Ibn Arabi’s spiritual and metaphysical teachings, encompassing 560 chapters of esoteric wisdom that have influenced Sufi thought for centuries7.

The significance of this edition cannot be overstated. For the first time, researchers and spiritual seekers alike have access to a text that has been meticulously verified against the earliest and most reliable manuscripts, including the famous autograph Konya manuscript written in Ibn Arabi’s own hand. This breakthrough comes after centuries of circulating editions that contained numerous errors and inconsistencies, some of which significantly altered the meaning of Ibn Arabi’s subtle teachings. The Yemeni edition, published in 2010 to coincide with Tarim being named the Capital of Islamic Culture, represents the culmination of decades of scholarly effort to reclaim the authentic voice of the Great Shaykh1.

Historical Context:

The Complex Legacy of Previous Editions

The publication history of Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya reveals a tortuous journey toward textual accuracy:

Bulaq Editions (1853-1857, 1876): The first printed editions emerged from Egypt’s Bulaq Press under the supervision of proofreaders Sheikh Ahmed Abu al-Reformer of Al-Abyari and Muhammad Qatta al-Adawi. These pioneering efforts were nevertheless marred by numerous errors due to their reliance on late manuscripts rather than original sources. Research indicates these editions created a hybrid text that mixed Ibn Arabi’s first and second recensions, unaware that the author had produced two distinct versions of his work5.

Standard Cairo Edition (1911): This edition, published again by Bulaq Press, marked a significant improvement as it attempted to reproduce the text of the Konya manuscript thanks to the investigative efforts of Emir Abd al-Qadir al-Jazairi. Despite this advancement, those supervising the printing did not directly consult the Konya manuscript but relied on a corrected copy that still contained arrangements errors and failed to highlight many of the book’s internal titles as Ibn Arabi had indicated in his original manuscript15.

Modern Scholarly Efforts

Osman Yahia’s Edition (1972-1992): The renowned scholar produced 14 volumes covering up to chapter 161, providing valuable comparative analysis between manuscripts but creating what Claude Addas and Julian Cook describe as “a hybrid text” that did not systematically follow the Konya holograph. Yahia made strenuous efforts in controlling the text and creating introductions, subtitles, and indexes, but his work was not devoid of errors15.

Ihya al-Turath and Dar al-Kutub Editions: These late 20th-century editions offered modern formatting and clear presentation but did not include any new study of the book’s manuscripts, essentially being attractive repackagings of the Cairo edition rather than critical new editions1.

Editorial Methodology:

The new Yemeni edition employs a sophisticated methodology that sets it apart from previous efforts. Editor Abd al-Aziz Sultan al-Mansub has undertaken a comprehensive approach that respects the principles of modern textual criticism while understanding the unique challenges presented by Ibn Arabi’s complex mystical terminology.

Manuscript Sources

The edition is remarkable for its inclusive approach to source materials:

Konya Manuscript (MS Evkaf Muzesi 1845+): This autograph manuscript, written in Ibn Arabi’s own hand (with the exception of volume 9), forms the primary foundation for the new edition. Completed in 1238, this 37-volume holograph represents Ibn Arabi’s second and definitive recension of the Futuhat, once part of the waqf of his stepson and foremost student, Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi25.

Sulaymaniya Library Manuscript: This important manuscript served as a crucial comparative text throughout the editorial process, providing additional verification for difficult passages and alternative readings.

Cairo Edition (1329H/1911): Despite its limitations, the standard Cairo edition was consulted extensively as it represented the first attempt to base the printed text on the Konya manuscript.

Osman Yahia’s Partial Edition: The portions published by Yahia (up to chapter 161) were consulted for their valuable footnotes and variants drawn from the Beyazid manuscripts, which correspond to Ibn Arabi’s first version5.

Table: Key Manuscript Sources for the New Critical Edition

| Manuscript | Type | Date | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Konya (Evkaf Muzesi 1845+) | Autograph holograph | 1238 CE | Ibn Arabi’s own hand, definitive second recension |

| Sulaymaniya Library | Copy | Unknown | Important comparative source |

| Beyazid 3743-3746 | Autograph of first version | 1231 CE | Represents Ibn Arabi’s first draft |

| Cairo Edition | Printed text | 1911 CE | First attempt to use Konya manuscript |

Structural Features

The new edition presents the complete text in twelve meticulously organized volumes, with each volume encompassing three of the original 37 books, except for the final volume which contains four. This thoughtful arrangement makes the vast work more accessible to scholars while maintaining the structural integrity of Ibn Arabi’s original organization1.

The physical presentation of the volumes respects the grandeur and importance of the content, with elegant typography and clear printing that does justice to the subtle complexities of Ibn Arabi’s prose. The publishers have maintained the original page numbering of the Konya manuscript alongside the new pagination, allowing scholars to reference both systems—a feature that greatly enhances the edition’s research utility1.

Extensive Indexing System

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of this new edition is its unprecedented comprehensive indexing system. Each volume contains detailed indexes of:

Quranic Verses: All citations and references to the Holy Quran are meticulously cataloged, allowing researchers to trace Ibn Arabi’s hermeneutical approaches to specific verses.

Prophetic Hadith: The traditions of the Prophet Muhammad are indexed with their complete chains of transmission (isnads) and evaluations of authenticity.

Poetic Citations: Both Ibn Arabi’s original poetry and verses he quotes from earlier poets are systematically organized, providing insight into his literary influences and poetic sensibilities.

Sufi Terminology: The specialized vocabulary of Islamic mysticism is cataloged, offering a conceptual roadmap to Ibn Arabi’s technical language.

Historical Figures and Places: Names of scholars, saints, geographical locations, and historical events are indexed, contextualizing Ibn Arabi’s thought within its historical milieu.

Cited Works: The many books and treatises referenced throughout the Futuhat are listed, revealing the extent of Ibn Arabi’s scholarly engagement.

Sects and Groups: Various Islamic sects and spiritual communities mentioned in the text are cataloged, reflecting the religious diversity of Ibn Arabi’s intellectual world1.

Textual Corrections and Scholarly Improvements

One of the edition’s most significant contributions is its meticulous correction of errors that had accumulated in previous editions. As the editor notes in his introduction to the edition, earlier versions contained numerous mistakes—some accidental through scribal error, and others potentially intentional through ideological opposition to Ibn Arabi’s teachings1.

For example, on page 74 of the first volume, where previous editions read: “The facts are now in judgment (=in the eye), as they were in science,” al-Mansub recognizes that the addition “(=in the eye)”—first appearing in Osman Yahia’s edition—represents a dangerous confusion of Ibn Arabi’s precise technical terminology. The words “al-hukm” (judgment) and “ayn” (eye) represent entirely different concepts in Ibn Arabi’s metaphysical system, and such conflations distort his careful distinctions1.

Preserving Ibn Arabi’s Structural Intentions

Previous editions often failed to respect Ibn Arabi’s own organizational scheme, particularly his use of internal titles and section divisions. The new edition carefully restores these structural elements, allowing readers to appreciate the sophisticated architecture of Ibn Arabi’s encyclopedic work. The original manuscript’s paragraph divisions have been scrupulously maintained, correcting instances where earlier editors had erroneously divided single paragraphs into multiple sections1.

Impact on Ibn Arabi Scholarship

Benefits for Researchers and Translators

This critical edition arrives at a propitious moment in Islamic studies, as interest in Ibn Arabi’s thought continues to grow globally. For scholars at the Ibn al-Arabi Foundation and elsewhere, it provides an unprecedented reliable foundation for:

Academic research: Scholars can now confidently cite passages knowing they reflect Ibn Arabi’s original words rather than scribal interpolations or printer’s errors.

Translation projects: The Foundation’s ongoing project to produce the first complete Urdu translation of the Futuhat—as well as other translation efforts like Eric Winkel’s English translation—will benefit immensely from this authoritative Arabic text311.

Textual analysis: Researchers tracing the development of Ibn Arabi’s thought between his first and second recensions now have a solid basis for comparison.

Integration with Digital Humanities

The comprehensive indexes make this edition particularly suitable for digitalization and computational analysis. As the Ibn al-Arabi Foundation develops its specialized library and manuscript archive, this edition will serve as the cornerstone for a complete digital ecosystem around Ibn Arabi’s works, facilitating advanced searches, conceptual mapping, and intertextual research that was previously impossible3.

Conclusion:

The publication of this critical edition of Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya by Yemen’s Ministry of Culture represents more than just another academic achievement—it constitutes a reclamation of intellectual heritage and a restoration of Ibn Arabi’s authentic voice. For too long, students of the Great Shaykh have struggled with unreliable texts that obscured rather than revealed his profound spiritual insights.

Under the skilled editorship of Abd al-Aziz Sultan al-Mansub, this edition achieves what previous efforts could not: a comprehensive, accurate, and scholarly rigorous text that honors Ibn Arabi’s legacy while making it accessible to contemporary readers. The meticulous attention to manuscript sources, the comprehensive indexing, and the thoughtful corrections of historical errors together establish a new standard for editions of classical Islamic texts.

The Ibn al-Arabi Foundation celebrates this achievement as a monumental step forward in its mission to preserve and disseminate the teachings of Shaykh al-Akbar. As the Foundation continues its work on translations, publications, and educational programs, this edition will undoubtedly serve as the foundational text for all future engagement with Ibn Arabi’s magnum opus. It invites scholars, students, and spiritual seekers alike to experience the Meccan Revelations in their pristine form, as their author intended them to be read and understood.